The First Reformed Church at 9 Bayard Street in New Brunswick not only serves as one of the most historic buildings in New Brunswick, but as the final resting place for Theodore Frelinghuysen. The only problemis that the whereabouts of the grave of Mr. Frelinghuysen, seventh President of Rutgers University (then Rutgers College) & former US Senator from NJ, is unknown as it has been lost to the weathering of the cemetery and the neglect from the caretakers. However, the lack of a physical object does not mean that Mr. Frelinghuysen’s body is not buried at the Dutch church’s resting site, nor does it take away from the accomplishments of this man that are owed to the Dutch dynasty he was a central figure of.

(Not pictured: Theodore Frelinghuysen’s headstone)

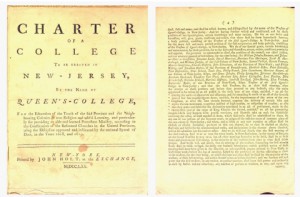

Theodore J. Frelinguysen, Theodore’s great-grandfather, served as the minister of the First Reformed Church in New Brunswick and was central to the First Great Awakening, and with that, the spread of Dutch-influenced Christianity. Additionally, as part of the Church leadership position, TJF was very involved in the founding of Queen’s College and Theodore’s father served in the Revolution, and many of his relatives were influential in local politics and the goings of daily life. In New Brunswick, the Frelinghuysens were the Kennedys. With this inevitability on his shoulders, Theodore attended the College of New Jersey (now Princeton) and practiced law with his brother and Richard Stockton, whose name recognition rings just as true today as it did then.

Frelinghuysen flourished in the political sphere in which he served as US Senator from New Jersey and had many of his votes and political actions influenced by his religion and Dutch roots. He was even the vice-presidential candidate under Henry Clay in the 1844 Presidential Election. Frelinghuysen was an abolitionist when it was unpopular to do so, and his path eerily followed the beginnings of Abraham Lincoln’s: “a lawyer, a politician, a Whig-turned-Republican… had a strong religious commitment and personally found slavery immoral… sought to preserve the Union and hesitated to follow the abolitionist line of denunciation of the South.” (Eells 68). Unfortunately, Theodore didn’t try again for higher office, but he did return to his New Brunswick roots to serve as the seventh President of Rutgers after his stint at New York University.

The shame about Frelinghuysen’s missing grave is that it could have been one of the few monuments to the man and his career. Buildings around Rutgers bear his family’s name, such as the dormitory or the street, but that is not directly Theodore’s honor to be had. In fact, it seems much of what Theodore stood for was something that should have been remembered, or at least recognized to be significant during his time, which is one of the main reasons we wished to recognize his achievements. Accounts of Frelinghuysen’s speeches on the floor of Congress remember him as a passionate, reasoned man who represented his constituents well, so he deserves, if not a grave, a marker of his significance to the nation and our community here in New Brunswick.

Sean Giblin, Laura Friedman, Evan Pié (Section 10)