1609 Freedom of the Seas and Modern Implications

Jeanne Ryder

What is it?

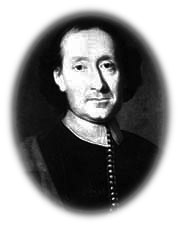

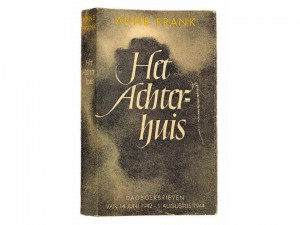

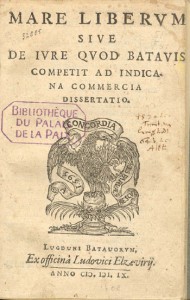

Mare Liberum written by Hugo Grotius inspired the most successful international organization of our age – the United Nations. At 540 United Nations Plaza in New York, New York, discussions and compromises about international relations can be heard on the daily. This building – so close to home – serves as the headquarters for the entire United Nations, a location that bears great pride for the entire tri-state area. Much of the thanks for this tremendous honor should go to the Dutch jurist, Hugo Grotius. He is generally known as the father of international law, thanks to the legal and philosophical ideas he shared in the several books he published. This post looks closely at his book Mare Liberum and the affects that it had on the development of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). This book, published in 1609, birthed the concept of “freedom of the seas” that now dictates international law regarding water passages.

Why is this important?

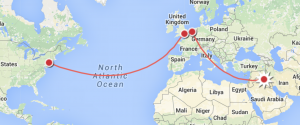

The Dutch have influenced American legal proceedings in a plethora of ways – from the original Democratic roots of the Mayflower Compact to the corporate laws surrounding modern day capitalism. The Dutch were generally more progressive than their surrounding countries – especially during the Dutch Golden Age that characterized the 17th century. It was during this Dutch cultural peak that Hugo Grotius first elaborated on his ideas of open sea territories. As he claims, “Every nation is free to travel to every other nation, and to trade with it” (Grotius 7). Grotius later served as a counsel for the Dutch East India Company in their legal trouble with Portugal following the seizure of the Santa Catarina ship, putting his ideas to the test. Clearly they survived the case, and even outlived time as his principles are executed everyday on the open seas. His revolutionary ideas about border endings transcended basic trading laws to serve as a guide for the multi-governmental organization we know as the United Nations today. Grotius did not believe in the claiming of water for two of the following reasons: “First, it is not susceptible of occupation; and second its common use is destined for all men. For the same reasons the sea is common to all, because it is so limitless that it cannot become a possession of any one, and because it is adapted for the use of all, whether we consider it from the point of view of navigation or of fisheries” (Grotius 28). In the 1920s, national claims in waters was brought to the table of the League of Nations (first attempt of international law) as nations (including the Netherlands) wished to extend borders to include mineral resources, protect fish stocks and control pollution. Several nations met at the Hague in Holland to discuss the matter – where Dutch jurist Cornelius van Bynkershoek’s “cannon shot rule” was used to make borders extend 3 nautical miles into the water. The Dutch are inseparable from both American politics and the universal politics we see today. It is no coincidence that 2 of the 6 hosting cities of the UN are Dutch and American. Actually, the Hague was considered for the headquarters of the UN but John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s 8.5 million dollar donation to purchase the land in Manhattan swayed the architects. Instead the International Court of Justice and the International Criminal Court remain in the Hague today, since the Netherlands philosophical and legal developments were crucial in the foundation of international relations. Today, Dutch and American government officials are crucial for the carrying out of compromises between nations in the UN, thanks to the originally Dutch principles that have been carried over into the American political system. Open seas are especially important today considering problems like the GPGP (Great Pacific Garbage Patch) and the lack of responsibility for oceanic pollution. UNCLOS is working hard to find a solution, but would never have been able to do so without Hugo Grotius’s Mare Liberum.

Works Consulted

David Armitage, “Introduction”. In: Hugo Grotius (2004) The Free Sea, Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, pp. xxii–xxiii.

Grotius, The Freedom of the Seas.

“Lake Success: A Reluctant Host to the United Nations”. Newsday (New York). Archived from the original on May 23, 2006.

Tullio Scovazzi lecture entitled The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea and Beyond in the Lecture Series of the United Nations Audiovisual Library of International Law

http://www.un.org. Accessed April 11, 2016.

![[Edin, Janin, Jim] Via Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.00 https://www.flickr.com/photos/edenpictures/4980993330/in/photostream/](http://sister-republics.blogs.rutgers.edu/files/2016/04/4980993330_052c62a094_m.jpg)