By: Mansi Adroja, Lizbeth Cespedes, Ananya Mondal, Madhuri Bhupathiraju, and Tanya Banerjee

Section: 5

Castle by A River is an oil piece painted by Dutch artist, Jan Van Goyen, in 1647. Goyen was a landscape artist who painted this particular scene in the Netherlands. In 1964, Edith Neuman de Vegvar gifted the painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, where it currently resides.

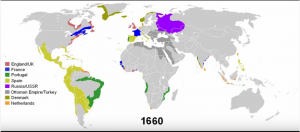

We chose this particular painting because it is an eye-catching depiction of rivers, and it encompasses their importance to the Dutch economy and life. During the late 16th century, as the Dutch Republic started to become a distinct entity and form a distinct culture, Dutch paintings also began to show a similar representation of the country. Many paintings included seascapes which represented the “naval and trade power”, which was popular among the Dutch Republic.

By juxtaposing the fisherman with the castle in the background, the painting distinguishes the working class from the wealthy. This piece is also an example of how during the Golden Age, art transitioned from depicting religious aspects to portraying political viewpoints and everyday lifestyles. This shift reflected the change in the focus of the country from religious to secular themes as well as the economic growth taking place during this time period.

People today can connect to this painting through its deep roots in Dutch history and culture. It reminds viewers of some of the core foundations of a civilization–perseverance and work ethic. These values are not limited to any one country; they are universal.

The following is a short, interesting analysis of the castle’s “identity” and the choice of colors in Goyen’s painting: “The subject and composition of this picture recall Jan van Goyen’s many views of Nijmegen, but the fort here, with its Romanesque bell tower, improbable portals, and asymmetrical façade, is surely imaginary. The work is remarkable for the warmth of its brown and yellow tones, with rose and salmon colors throughout the cloudy sky.”

A major part of the painting is the stormy sky. Goyen uses a yellow and brown color scheme for most of the landscape and subtle pink tones for the sky. Although there is an emphasis on the castle in this painting, Goyen interestingly employs perception to also accentuate the boat with three fishermen in the foreground.

Sources:

- “Castle by a River by GOYEN, Jan Van.” Castle by a River by GOYEN, Jan Van. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Apr. 2016.

- “Castle by a River.” Metmuseum.org. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Apr. 2016.

- “History of Dutch Golden Age.” Holland.com. N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Apr. 2016″

- “Jan Van Goyen’s River Landscape (Pellekussenpoort near Utrecht).”Jan Van Goyen’s River Landscape (Pellekussenpoort near Utrecht). N.p., n.d. Web. 6 Apr. 2016.