By: Sharon Kang, Rose Kostak, Cynthia Tsai

The Vanderveer House

The original part of the Vanderveer House shows Dutch and English traditions of vernacular construction. It is a one and a half story clapboard frame dwelling. The original fabric of the house is still intact today, and the original flooring is of wide pine boards. A wall in the west parlor features raised wood paneling above the fireplace with a barrel-back cabinet to the side. The house had a few alterations later in the 19th and 20th century such as imposing “bungaloid” features like exterior stucco. The interior of the house interprets both the west Georgian section when Knox were in residence and also the east Federal addition with its higher ceilings.

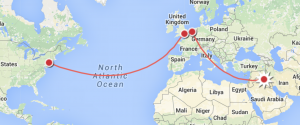

The Vanderveer House is located in Bedminster Township in Somerset County, along the North Branch of the Raritan. It served as headquarters for General Henry Knox during the Revolutionary War’s Second Middlebrow Encampment and is the only known building still standing that was associated with the Pluckemin Artillery Cantonment. It is also the last surviving building in Bedminster associated with the Vanderveer Family. The Vanderveer family was prominent in Bedminster Township history from its earliest settlement through the mid 19th century. The location has never moved, and the house is now used as a museum and an educational center. It was first built in the early 1770’s by Jacobus Vanderveer, the father of Jacobus Vanderveer Sr., who built it for his son and other Vanderveer families to come. It was then purchased by the Township of Bedminster in 1989 and has experienced many changes in construction since then, although remains of the original framing still exist and endure in sturdy condition. Jacobus Vanderveer was descended from Dutch immigrants who arrived in Long Island, New York in 1659. He was a very active member of the Dutch Reform Church of Bedminster, acting as an elder in the church and playing a major part in the organization of the church. He even donated the land that the church was built on, and eventually married Mariah Hardenbergh, the daughter of Jacob Ruten Hardenbergh, who was the minister of the church. The Dutch Reform Church was a huge part of Dutch life in America, and Jacobus Vanderveer was a big player in the church.

The Vanderveer House is connected to Rutgers history because Jacobs R. Hardenbergh, Jacobus Vanderveer’s father-in-law, was Queen’s College’s first President. Its first instructor was Frederick Frelinghuysen, and through intermarriages, Frederick Frelinghuysen and Elias Vanderveer were brothers-in-law. The Vanderveer’s strong connections to Frelinghuysen portray that the family was strongly linked with Dutch-American cultural elites.

We picked the Vanderveer House because it is very close to where one of our partners, Rose, lives in Morris County and it is interesting how such an influential historical monument could be located only a short drive away from home. It is also fascinating how so much information can be gathered about a building that at first glance appears to be like any average one-story house but in reality was reconstructed multiple times so that it now retains most of the original Dutch framework and holds the appearance of the Vanderveer House from when it was first built. This object brings many aspects of Dutch life to light, specifically the connection to the Dutch Reform Church, which played such a large role in the history of the house. The Dutch had such an influence in America, especially in our area and at Rutgers University, and continues to be a legacy to many families here, and this house perfectly exemplifies their life and their culture. It tells a story that parallels many whose ancestors may have come here not only from the Netherlands, but also from other places in Europe and maybe even from elsewhere in the world.

“The Vanderveer families remained in the Pluckemin/Bedminster area for generations and are remembered today as major contributors to the legacy of the area.” (www.jvanderveerhouse.com)

Bibliography

“Guardians.” The Pluckemin Cantonment and Jacobus Vanderveer House in Bedminster New Jersey. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2016.

“Jacobus Vanderveer House and Museum.” Jacobus Vanderveer House and Museum. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2016.

“The Vanderveer House.” The Vanderveer House. N.p., n.d. Web. 13 Apr. 2016.

![[Edin, Janin, Jim] Via Flickr [CC BY-NC-ND 2.00 https://www.flickr.com/photos/edenpictures/4980993330/in/photostream/](http://sister-republics.blogs.rutgers.edu/files/2016/04/4980993330_052c62a094_m.jpg)