by Marina Shimarova and Soo Jeong Hwang

Section 12

The week we were in the Netherlands was Boekenweek, a week dedicated to Dutch writing. The National Book Week is put together by the Foundation Collective Propaganda for Dutch Book. Each year, CPNB foundation hosts two writers to compose an essay and a gift.

SH: I was interested in this topic because I grew up with a Dutch character named Nijntje, or Miffy. I got interested in how much the Dutch literature was present in my life and wanted to look more into the topic.

MS: Literature is something that can reach across cultures in unexpected ways. As someone who grew up between two different cultures, I didn’t find many ways that the literature of the country where I was born overlapped with the literature of the United States. I was curious to find out if there was more in common between Dutch and American folklore due to their shared history.

“Rip van Winkle” was written by American author Washington Irving, Scottish-English by heritage. The tale is set in a Dutch town in Catskills, New York, where the author had not visited before he wrote the story. The story was published in Irving’s The Sketchbook 1819 – 20 and is set in the time period before and after the American Revolution. It concerns the story of a man who goes up the Catskill Mountains and meets with people who are playing ninepins who offer him a drink. van Winkle falls asleep and wakes up twenty years later. He goes back to his town and finds that his wife has passed away, his children have grown up and, that the American Revolution has taken place. The people in the town are amused by the story he tells. The Sketchbook was published in New York by C. S. van Winkle.

Irving’s tale features a Dutch main character, which shows the influence of the Dutch on American history. Furthermore, the plot of “Rip van Winkle” is similar to that of a classic European fairy tale. Its plot is based off of one of Grimm’s fairy tales. Rip van Winkle resonates with us to this day. The storyline can be found in modern popular media. Examples include “The Rip Van Winkle Caper” in The Twilight Zone and “Rip Van Flintstone” in The Flintstones.

The flying Dutchman is a well known character in American folklore. According to the legend, the Dutchman, supposedly named Vanderdecken, was the captain of a ship trying to sail around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. In the gale of a forceful storm, the captain refused the pleas of his crew and passengers to turn around to safety. Then, a ghostly figure appeared on board the ship, and condemned the captain to forever haunt the seas with a ghostly ship, as a punishment for his reckless behavior. Contrary to the name, the legend of the flying Dutchman originated in England, not the Netherlands. It was based on a 17th century Dutch sailor named Bernard Fokke, who was known for being able to travel from the Netherlands to Java with incredible speed.

[The Flying Dutchman by Howard Pyle]

The Sandman, named Klaas Vaak in Dutch literature, is the basis for the American comic book series by Neil Gaiman. The character of the Sandman also appears in American films such as Dreamworks’ “Rise of the Guardians” and songs like “Enter Sandman” by the band Metallica.

In the literature of the Netherlands and other Northern and Central European countries, the Sandman is a man who sprinkles dust and sand in the eyes of children to make them go to sleep.

[Cover of the Sandman comic books series]

[Klaas Vaak]

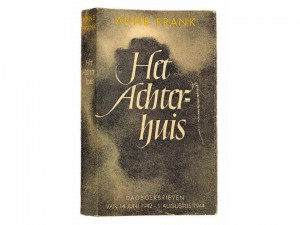

Anne Frank’s diary was published as Het Achterhuis (The Secret Annex) in the Netherlands on June 25th, 1947. The Anne Frank House in Amsterdam became a museum in 1960 and Otto Frank, Anne’s father, was involved with the House and campaigned for human rights and respect until he died. It is read across the world today, including the U.S. as we educate people about World War II and the Holocaust. The resounding effects of honesty and human nature found in Anne’s diary is loved and respected by many people over the world.

[The first edition of Anne’s diary]

Sources

Pierre M. Irving, The Life and Letters of Washington Irving, G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1883, vol. 2, p. 176

http://www.britannica.com/topic/Rip-Van-Winkle-short-story-by-Irving

http://www.biography.com/people/washington-irving-9350087#profile

http://www.nyfolklore.org/pubs/voic36-1-2/st-rip.html

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0734674/

http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0580221/plotsummary?ref_=tt_ov_pl

Wright, Charlton, “The Phantom Ship; or, The Flying Dutchman,” Tales of the Horrible; or, The Book of Spirits (London: Charlton Wright, 1837), pp. 49-56.

Minnaard, Liesbeth (2009). New Germans, New Dutch: Literary Interventions. Amsterdam UP. p. 253. ISBN 9789089640284. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

http://www.occultopedia.com/f/flying_dutchman.htm

Gaiman, Neil (w). “The Origin of the Comic You Are Now Holding (What It Is and How It Came to Be” Sandman 4 (April 1989)

http://www.efteling.com/SprookjesmusicalKlaasVaak

http://www.annefrank.org/en/Anne-Frank/The-diary-of-Anne-Frank/Anne-Franks-diary-is-published/

http://www.annefrank.org/en/Anne-Frank/Anne-Franks-history-in-brief/